In the current battle between Israel and the Islamist militants, both display a new level of commitment to destroying the other.

The long history of the Israeli-Palestinian conflict is filled with bloodshed, dislocation and trauma. But even by those relative standards, the current conflagration stands out. For one thing, it’s especially brutal. Not since the Holocaust have as many Jews been massacred at one time as were on Oct. 7, when Hamas militants stormed Israel, killing 1,400 people and taking more than 200 hostage. Before Israel escalated its ground operations in the Hamas-run Gaza Strip, its retaliatory strikes, mostly from the air, killed more than 7,700, according to Gazan authorities, and dislocated nearly half the population of 2.3 million, by an estimate of UN officials. Israel’s decision to cut off power to Gaza — and severely limit water and food supplies — threatens a larger humanitarian calamity.

Beyond that, this new chapter has changed the way Israelis see the threat from the Islamist group, and thus the measures they’re prepared to take against it. From the start, Hamas, which the US and European Union designate a terrorist organization, has been dedicated to the destruction of the state of Israel. For three decades, it’s held to that mission as other Palestinian leaders have committed to peaceful coexistence with Israel while pursuing their own state alongside it. Hamas considers all of the Holy Land — which encompasses what today is Israel, the West Bank and Gaza — a divine Islamic endowment, and pledges in its charter to destroy Israel by any means. After Hamas showed what it’s capable of on Oct. 7, Israelis now say they are determined not just to suppress the group but to dismantle it, a goal that will entail more bloodshed and may not be achievable.

How We Got Here

The modern struggle between Arabs and Jews over ownership of the Holy Land is rooted in the nationalism that grew among both groups after the World War I-era collapse of the Ottoman Empire, which had ruled the territory for centuries. In 1920, the war’s victors gave the UK a mandate to administer what was then called Palestine. Intercommunal fighting in the territory was exacerbated by resistance among Arabs to Jewish immigration, which rose in the 1930s; in the face of Nazi persecution, increasing numbers of Jews from abroad sought sanctuary in their ancient homeland, where Jews have lived for nearly 4,000 years.

Read More: Understanding the Roots of the Israel-Hamas War

In an effort to stop Arab-Jewish violence, a British commission in 1937 proposed partitioning the territory to create a state for each group. A decade later, the United Nations endorsed a different division. The Arabs said no both times, while the Jews said yes. After declaring its independence in 1948, Israel was attacked by neighboring Arab states, and its wartime gains established the borders of the new nation. The Palestinians use the term Nakba, or disaster, to refer to this period, which produced an estimated 700,000 Palestinian refugees. Many of them fled to the Gaza Strip, then under Egyptian control.

In a subsequent 1967 war, Israel captured the rest of what had been Mandatory Palestine — Gaza plus the West Bank — and put Palestinian residents of the territories under military occupation. The Palestine Liberation Organization (PLO) came to prominence after that war, launching guerilla attacks on Israel and earning international recognition as the representative of the Palestinian people.

Read More: What is Hamas, the Militant Group That Attacked Israel

The first popular uprising, or intifada, against the occupation began in 1987, giving rise to Hamas. The group initially gained popularity among Palestinians by establishing a network of charities to address poverty as well as health care and educational needs. But it made its main mission clear: the destruction of Israel.

How Two Peoples Could Have, and Have Split the Holy Land

While the PLO had the same goal at the time, the secular group shifted its views. Having lost its forward bases in Lebanon after Israel invaded in 1982 to remove them, the group in the late 1980s tacitly recognized Israel’s right to exist. As the toll of the intifada accumulated, Israel engaged in secret peace negotiations with the PLO, which produced the 1993 Oslo Accords. The PLO recognized Israel’s legitimacy, and, as an interim measure, Palestinians gained limited self-rule, administered by a body called the Palestinian Authority.

In subsequent years, trust between Israelis and Palestinians eroded. Hamas launched attacks and suicide bombings in Israel, and Israelis continued to expand Jewish settlements in the territories. Israeli and PLO negotiators repeatedly failed to reach a promised permanent agreement that would have presumably established a Palestinian state. A second intifada, from 2000 to 2005, was bloodier than the first.

With negotiations at a standstill, Israel in 2005 unilaterally withdrew its remaining forces from Gaza and uprooted Israeli settlers from the strip, while maintaining control of its airspace, maritime territory and entrances into Israel. The next year, Hamas defeated the PLO’s main faction, Fatah, in Palestinian legislative elections. After months of fighting between the two groups in Gaza, Hamas gained control of the territory in 2007 and since has used it periodically to launch rocket attacks and raids on Israel. Fatah continues to dominate the Palestinian Authority, which is responsible for limited self-rule in the West Bank. Alarmed by the Hamas takeover, both Israel and Egypt imposed tight restrictions on goods and people moving in and out of Gaza — measures referred to as the blockade.

In recent years, Israel had taken limited steps to ease the constraints, including issuing permits for 20,000 Gazans to work inside Israel, where they could earn 10 times what they would at home. It was commonly believed in Israel that Hamas was focused on improving Gaza’s economy, and that even if violence erupted from time to time, the threat Hamas posed could be contained to an acceptable level. Then came Oct. 7.

Hamas’s Assault on Israel

The attack on Israel that day began with a barrage of rocket strikes launched from Gaza. As the sun rose, several thousand heavily armed Hamas militants burst out of the strip, mostly through holes they had blown in the fencing along the border with Israel. Some used paragliders or infiltrated by sea. They penetrated army bases and attacked towns as well as a music festival in the desert, seemingly with the sole purpose of killing or taking hostage as many Israelis as they could.

Impact of the War on Southern Israel

Note: Conflict events from Oct. 9-25

After invading fighters returned to Gaza or were killed or captured, Hamas continued to fire rockets into Israel, some 7,000 of them, according to Israel’s military. So far, the vast majority have caused little or no harm, largely because of Israel’s Iron Dome air defense system, which the military says has an intercept rate of about 90%. Yet such barrages can be deadly — they killed 12 Israeli civilians in 2021 — and send people rushing to bomb shelters when an alert warns of incoming rockets.

Israel’s Response

The larger immediate perils have shifted to the Palestinians in Gaza, who are facing Israel’s furious response to Oct. 7. While Israeli officials say that their goal is to protect the country by permanently eliminating the threat posed by Hamas, President Isaac Herzog’s comments in a CNN interview, in which he said he held “an entire nation” responsible for Oct. 7, gave weight to accusations, by among others a UN panel of experts, that Israel was exacting collective punishment.

Destruction in Gaza

Key civilian facilities are within or near areas with the most damage

Note: For highlighted facilities the map shows all buildings, not single compounds. The center point for each building is shown.

In the wake of the attacks, Israel cut off supplies of water, electricity, fuel and food to Gaza, while pulverizing its homes, buildings and infrastructure with air strikes. It later agreed to resume some water service. Israel dropped leaflets from planes encouraging people in northern Gaza to move south to avoid the bombardment, and then bombed the south, launching at least 400 rockets on Oct. 24 alone. After two weeks, Israel agreed to allow limited amounts of relief supplies to be trucked in from Egypt. United Nations officials say that nearly 1.4 million people have been displaced, which they say is 2.5 times the number that can be accommodated.

Three weeks after the Hamas attack, after a major push into Gaza by Israeli ground forces, Prime Minister Benjamin Netanyahu announced a “second stage” of the war, which he said would be “long and difficult.”

Looking Ahead

As the fighting escalates, Gaza is poised to suffer considerably more devastation. Even before the most recent conflict, the economy and welfare were in decline, with conditions worsened by the blockade of the last decade and a half. A UN assessment last updated in August said 81% of Gazans were poor and cited an unemployment rate of 47%.

Gaza’s Economy Before and After Israeli and Egyptian Blockade

The poverty rate increased 26 percentage points over 16 years, and investment as a share of overall GDP in the territories fell by 7.6 points

Source: United Nations Conference on Trade and Development

Surviving refugees from 1948 in addition to their descendants make up about 81% of the strip’s population today. With economic activity limited, many still rely on UN rations. Most tap water in Gaza is undrinkable, forcing households to buy desalinated water from private vendors. Even before Israel enforced its siege, power outages were common.

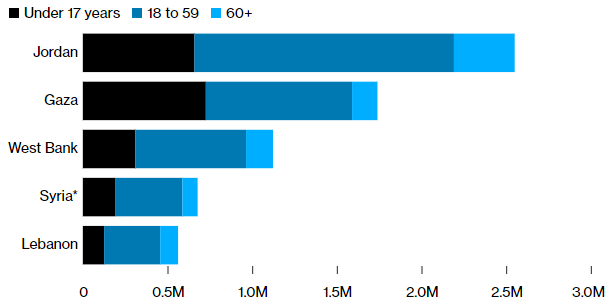

Palestinian Refugee Populations

Gaza is home to more than a quarter of all registered Palestinian refugees from the 1940s, which includes descendants of those who fled the war

Source: United Nations Relief and Works Agency for Palestine Refugees in the Near East

Prior to the current war, Israel and Hamas fought half-a-dozen major military confrontations centered on Gaza, and engaged in a number of smaller clashes. The recurring violence is particularly rough on children in Gaza, where 47% of the population is younger than 18. A report in 2021 from the advocacy group Euro-Med Monitor found that nine out of ten children in Gaza suffered some form of conflict-related trauma.

The war’s political fallout among Gazans won’t be known for some time. In 2014, just after Israel and Hamas fought their previous confrontation that comes closest to this one in ferocity — more than 2,100 Palestinians were killed and the strip suffered massive destruction — the Islamist group saw its popularity momentarily surge.

Support for Hamas is Higher in Gaza Than in the West Bank

Percentage of poll respondents who said they would support Hamas in a new legislative election

But a month later, polling showed Palestinians expressing dissatisfaction with the war’s achievements in light of its costs. Hamas’s standing began a decline that didn’t stop for another four years. The group got a more sustained boost after a bout of fighting in May 2021, but that was much more contained and far fewer Palestinians died.

It’s impossible to know what those trends might mean for today’s conflict as there hasn’t been one like this before. But the ways in which Palestinian attitudes are being shaped by the current tumult will surely play a role. In their promised invasion of Gaza, Israeli forces aim to capture or kill Hamas members and to dismantle the group’s war-making capacities because, officials say, their citizens can’t live next to a group that is plotting their murder. But more than men or weaponry, Hamas is an idea. Whether that idea survives Israel’s onslaught and inspires a new Hamas, or perhaps an even more radical successor, will depend on how the Israelis prosecute the war — but also on how the Palestinians ultimately come to regard the group that triggered this bloody new chapter.

TRY 2 WEEKS FREE our Automated Trading and Investment Management Services